The Maps of King Arthur?

← Back to main index

The Maps of King Arthur?

This section is only of moderate importance for the history of portolans. Rather it shows possible links with less known details of medieval and early modern discoveries. Besides the possible relation with portolans it opens further questions on the history of records. It seems the origin of the portolans was not the only issue shrouded in silence.

The Map of the North

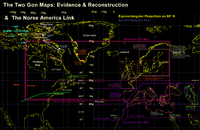

Reconstruction of the early medieval portolan source. A chart with two maps on the same side. It was the final result of the Pizigani cartometric.

An equirectangular projection based on 50° N has no distortion along the 50° N parallel. Therefore the projection base is usually at the center of a map. The highly odd thing was that both northern maps began north of the 50° parallel: the "Caerte van Oostlant" at 50.5° N and the "Carta Marina" at c. 53° N. It is now evident that these two maps were at some time before part of a larger map that went south of 50° N. It is hard to say how far south, but 45° N or 42° N (northern Spain) is a possibility.

It seems that the southern portolan area was transmitted completely but part of the northern portolan area was lost. A complete northern map or map set may still be extant in 1532.[1]

The Location Hint

A projection of the southern map on 36° N makes sense. It resulted in the least distortions for the Mediterranean. The northern map went north at least to 75 gon, c. 68° N. A center at 50° N would suggest a southern extension to 32° N. But it probably went not further down than 39° N (43 gon).[2]

Still the 50° N base is not at the center of the map. But it is directly along the English Channel. A reason for an off center base would be to keep the distortion low in the most trafficked area near one's own ports and at one's own homeland. So the creator of this map probably lived along the Channel coast in southern England or northern France.

The Time Window

The creator of these two maps had to live close enough to classical times to know the Gon grid (now supposed to be used by late Romans) and the mathematics of the equirectangular projection. But he had only a pinax world map as source.[3]

He no longer had the book to the pinax with the detail maps nor a detail map of the Mediterranean. That points to a considerable time span of book burning, say at least 100 years. The large scale burning of classical books began around 370 and lasted for centuries. So the time window opens around 470.

It may close around 600. The most important scientist of this time, Isidor of Seville (560 - 636), thought the earth to be a flat disc.[4]

During the later 6th century, England faced an extreme decline in the quality of pottery. In 625 even a king or high noble was buried with a crude clay bottle, and the pottery wheel was no longer in use.[5]

That level of civilization does not fit mathematics for equirectangular projections. The creation of the "Luxeuil-Euclid" falls inside this time window. It is a Latin version of Euclid's "Elements" dated to the late 5th century. The "Elements" were sufficient for the projections. The origin of this codex is a mystery but currently supposed to be somewhere in France.[6]

The Magical Mathematician

The Christian authorities of the 5th century had laws to prosecute classical mathematics.[7]

Even among the most educated around 500 there was confusion of what was classical science and what magic. Cassiodorus called philosophers those who "say that one should venerate the sun, the moon and the other stars." Boethius, who translated Euclid and tried to translate the Almagest, was accused in a court trial to be a magician.[8]

To find some traces of our portolan cartographer in this time window we have to search not for a mathematician but a magician.

The King Arthur Legend

Merlin, King Arthur and the Roman heritage.

The previous analysis points straight to a mathematician at his court. Already in the first and defining book on this legend (by Geoffrey of Monmouth c. 1138) Arthur is known for a maritime endeavor - the conquest of Iceland. But according to another source he even conducted large naval operations to Greenland and the Canadian Arctic up to the North Pole.

In the analysis of the Caerte van Oostlant it was concluded that Geradus Mercator had knowledge about an ancient origin of the portolans. But his only direct reference to late antiquity I considered such fantasy that I thought it unworthy to mention. The new and very unexpected cartometric result from the Pizigani map and the above analysis changed my mind.

The Mercator Letter

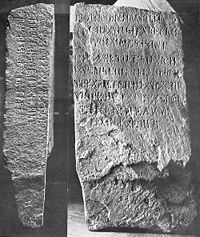

Two pages with fire damage of Mercator's 1577 letter to John Dee. (Click

here for full description.)

In spite of the damage this letter is the most puzzling document in modern geographic history. The results above suggest a new assessment of this letter.

The Cnoyen Report

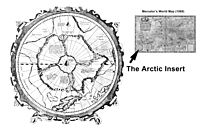

The Arctic map insert by Mercator in 1569. It caused the inquest by John Dee.

In his famous letter Mercator replied that he used a travel report of a "Jacobus Cnoyen" of Herzogenbusch (today in Belgium). Today nothing more is known of Cnoyen than what Mercator wrote here. It is supposed he lived in the 14th century. Mercator gave an excerpt of Cnoyens writing. Cnoyen mentioned three sources. One was the today lost book Inventio Fortunata "which book began at the last climate, that is to say latitude 54°, continuing to the Pole." The others were the Gestae Arthuri (lost too) and a meeting (of lost record) in 1364 at the royal court in Bergen with the king of Norway.

The Inventio Fortunata

The Cnoyen report was not an invention of Mercator. In 1507 Johann Ruysch drew a map with a similar Arctic and directly wrote there that the book "De Inventione Fortunatae" was his source. Cnoyen wrote that the Inventio Fortunata was written by a Minorite monk from Oxford "who was a good astronomer etc." and traveled the North with an astrolabe. He gave the book to the King of England, Edward III. His astrolabe he bartered for a bible with a priest. In 1364, this priest came with the astrolabe to the King of Norway and reported to him. The priest said (according to Cnoyen, cited by Mercator) that the monk with the astrolabe arrived in the North (probably Greenland) in 1360.

From the several mentions of the astrolabe it is clear that the priest and Cnoyen did know its purpose. It was used to measure the latitudes of visited places. With those numbers it was possible to reach every place again without an experienced guide. It was a way to concentrate several ships north or south of a coastal target for a sudden attack. The military impact of latitude was probably higher than of longitude in the 18th century. A book with latitudes of the Norse[12] colonies was almost invaluable for any foreigner.

A crucial point of the Cnoyen report received insufficient attention. Nowhere in what Mercator cited was any mention of the latitude of any place. Cnoyen had no latitudes. Therefore Cnoyen never had the opportunity to look in the Inventio Fortunata. The priest who reported to the King of Norway in 1364 mentioned none and mentioned no copy or excerpt that he made. So he probably had never had a chance to read it either. But therefore the description of the Inventio Fortunata as a description from "latitude 54°, continuing to the Pole." was only an assumption by Cnoyen.

In 1578 George Best, the second in command on Martin Frobisher's polar expedition,[13] wrote about the Inventio Fortunata. He did not use that name but:

- "This part of the world hath beene most or onely made knowen by the Englishmen's industrie. For, as Mercato mentioneth out of a probable author, there was a frier of Oxforde, a greate mathmatician,(1) who himself went verye farre north above 200 yeares agoe, and, with an astrolabe, described almoste all the lande aboute the Pole, finding it divided into foure partes or ilandes by foure greate guttes, indrafts, or channels..."[14]

- (1) An annotation probably by Hakluyt: "Nicholas de Linne, i.e., of Lynn in Norfolk, whose voyage to the Arctic regions in 1360 is quoted by Mercator in his map of the world dated 1569, from the Itinerary of Jacob Cnoyen of Bois le Duc, and also referred to by Dr. John Dee. See Hakluyt, vol. i, pp. 121, 122."

Some Norse America features in context with the northern gon map.

- "Hee reporteth that the south-weast parte of that lande is a fruitfull and a holesome soyle."[15]

That is definitely not in any record found by Taylor and suggests Best had read the Inventio Fortunata.[16] That land has to be further south and can only refer to Vinland below 43° N.[17] So from the only extant writer who read the book we know that the Inventio Fortunata had information well south of 54° N too.

We know from other people involved with the book that it contained information down to 18° N. The Inventio Fortunata is mentioned by "Christopher Columbus' son, Fernando, and the 16th century historian Las Casas. Both wrote that Inventio Fortunatae contained astonishing information about two floating islands far to the west on approximately the same latitude as the Cape Verde islands (18 degrees north)."[18]

According to a review of multiple sources by Kare Prytz (Columbus' son Fernando, las Casas, and an unknown sailor[19]), Columbus may have read the book and he may have had a copy on his first voyage.[20]

A Classical Book?

Of special interest in this regard are the writings of Turkish Admiral Piri Reis. He mentioned an unknown Spanish sailor who was with Columbus on three voyages and was captured by Reis' uncle.[21] Reis wrote an account of the sailor on his famous 1513 world map. Excerpt:

- "For instance, a book fell into the hands of the said Colombo, and he found it said in this book that at the end of the Western Sea [Atlantic] that is, on its western side, there were coasts and islands and all kinds of metals and also precious stones. The above-mentioned, having studied this book thoroughly,... The late Gazi Kemal had a Spanish slave. The above-mentioned slave said to Kemal Reis, he had been three times to that land with Colombo. ...These [Spaniards] were pleased and gave them glass beads. It appears that he [Columbus] had read-in the book that in that region glass beads were valued. Seeing the beads they brought still more fish. These [Spaniards] always gave them glass beads..."[22]

In 1526 Piri Reis wrote his "Bahriye", a famous illustrated sea atlas of the world. Here he mentioned Columbus' book again and suggested "on hearsay" that it was from classical times.[23]

America was known in classical times but the evidence is slim.[24] In our transmitted classical books there is none that describes America and neither is a lost one mentioned with such content. Even from medieval times we have no evidence that any such classical text existed. The only pre-modern book about America is Inventio Fortunata. It was not well-known in Europe and probably unknown to the Turks. Only this could be the book Piri Reis mentioned.

Kare Prytz reported in 1991 based on several sources[25] that in 1363[26] a Norse long ship[27] took a European looking priest from the coast of Yucatan back to his homeland. This long ship of course came from Vinland, went around Florida and crossed the Gulf of Mexico. There is some evidence that this was no single operation.[28]

Columbus first voyage - Intention and Result. (Click

here for full description.)

The relation of Columbus and the Inventio Fortunata may have left the attention of most historians because the biography by Fernando "has been «edited» by some translators. Important information about Columbus' knowledge of the far north and the fact that he read Inventio Fortunatae have been removed. So when in doubt, it is necessary to go back to the first edition of 1537." (Prytz).[29]

See also: A Map from the Inventio Fortunata

The Ivar Bardsson Link

In her 1956 paper, Taylor compared the Mercator letter with notes by John Dee and map inscriptions by Ruysch and arctic details from other writers. In the description of the polar area, Taylor noted similarities with the "Description of Greenland" by Ivar Bardsson (c. 1350) and by later 16th century reports. More recently some historians suggested that the priest who reported to the king of Norway in 1364 was Ivar Bardsson.[30]

It seems Bardsson was a key figure in rather obscure events around the end of the western Norse settlement in Greenland.

The Greenland Events 1341-1364

The two Norse settlements at Greenland were property of the king of Norway and only a royal ship, the "Knarr" was allowed to sail there. Any trade by others was under punishment.[31] The Knarr sailed not every year and a pause of 9 years was not unusual.[32]

- In 1341 the Bishop of Bergen dispatched an emissary, a priest named Ivar Bardsson, to visit the Bishop of Greenland.[33] The "Description of Greenland" is an account of this voyage by Bardsson.[34]

- In 1342 Bardsson was sent with a military force northwards to the western settlement. He reported that he found no humans, neither Norse nor Eskimos but only "horses, goats, cattle, and sheep," wild grazing between the empty houses. As Nansen pointed out, these animals could not survive a winter there alone. So the Norse settlers left only weeks before Bardsson arrived. There are no records of any later population there. In 2002 J. R. Enterline suggested Bardsson was a tax collector for the king and the church of Norway.

- "In 1342... inhabitants of Greenland" had "spontaneously deserted the true Christian faith and religion, ...repudiating all good morals and true virtues," and had turned to "the people of America... It is assumed that Greenland is located close to the western lands. By this it happened that Christians abstained from navigating to Greenland."[35] This was written down by the Icelandic bishop Gisle Oddsson in the 17th century. Possibly a record from memory shortly after a fire destroyed the church records of Skälholt in 1630.[36]

- On 1349 the bishop of Greenland died and Ivar Bardseen took over his duties.[37]

- In 1354 King Magnus of Norway ordered the judge and member of the Royal Council, Paul Knutson, to be commander of the Knarre. He shall choose soldiers of the king's personal guard and proceed with full authority to preserve Christianity in Greenland.[38]

The Kensington Runestone. Several 20th century scientists and scholars hold it to be genuine.

- In 1362 the Kensington Runestone was created in what is today Minnesota.[39] According to the inscription a group of 30 Norse[40] on an "acquisition journey from Vinland far to the west" lost "10 men red from blood and dead." Further they left "10 men by the inland sea to look after our ships fourteen days journey from this peninsula." By the local geography the "inland sea" was the Hudson Bay and they came along rivers to this place. Weapon and armor finds in the area suggest it was a well armed military party in a composition like suspected for the Knutson group.

- In 1364 Ivar Bardsson is recorded back in Norway.[41]

- In 1364 according to Cnoyen eight people from the other side of the "indrawing seas ... came to the King's Court in Norway. Among them were two priests, one of whom had an astrolabe..."

In 1738 a French expedition to the Pacific under de la Verandrye found in what is today North Dakota a stone structure with a small stone tablet that had runelike inscriptions.[42]

In that region de la Verandrye found a tribe later known as the Mandan. They built unique fortresses, had wooden houses in 9 towns and had agriculture. Some had white skin and blond hair.[43] A good part of the Mandan had gray hair and blue or bright brown eyes. They had a unique language and customs not related to any other North American Indian tribe.[44] "A fifth or a sixth of the Mandans has almost white skin and bright blue eyes."[45] Mandans were of European descent, they "are not Indians".[46]

According to their own myth their founder came as a white man with a canoe to the land.[47] De la Verandrye thought the Mandan were the remains of a military expedition centuries ago by a north European country.[48] Richard Hennig and other 20th century historians therefore thought they were the ancestors of the 20 Norse who survived Kensington and stayed in America with the Indians.

But that is impossible. An anthropologist was certain that 20 males could not transfer a sufficient genetic pool to maintain a highly visibly white population 400 years later. The original group had to have at least 50 to 100 persons and had to include women. It seems unavoidable that the Mandan were the lost Norse settlers from Greenland who "went to America".

In Greenland they were serfs of the king and the bishop. They were bound to their land and not allowed to settle elsewhere, especially not on the pagan continent. That would be a fall from Christianity. As the climatic conditions in Greenland deteriorated they may have searched for better land. Vinland was known but under control of the bishop of Greenland too.[49]

The only way to go was down the Hudson Bay. But they probably did not have enough ships to get the people and the animals down there. They had to send back a group from Hudson Bay to bring the animals down too. Bardsson may have left some soldiers there to capture at least part of this group. Then he had witnesses of the event and guides to the hiding place. Some of these prisoners must have guided the elite soldiers of Knutson to the area of Kensington.

Some others may have been taken to Norway to report to the king and to receive their punishment. The task of the Kensington soldiers was probably reconnaissance and capture of some settlers to prevent any repeat at the eastern settlement. Fear of that may have driven the settlers much further west than would otherwise be useful. The failure to capture them was a good reason to hide the whole story and destroy almost all records of it.

The Mountain and the Indrawing Seas

The Cnoyen report focused several times on "indrawing seas". It gives a definition that these are "rivers", according to Taylor up to 60 modern miles wide with strong currents.[50] Like George Best wrote in 1578, this is what we today call the channels, the straits or sounds of the Arctic. These indrawing seas begin beyond "Grocland" but nowhere in the report Greenland is mentioned. In a note John Dee wrote that Grocland is probably another name for Greenland. That seems correct, because Grocland is mentioned to be settled along with Iceland.[51]

The Cnoyen report said the currents in the indrawing seas were always to the north and so strong that no ship caught by them can ever sail back. This is not true, the main currents are towards the east and southeast.[52] It seems someone wanted to discourage any sailings there.

Taylor suggested similarities between the Cnoyen report and in Ivar Bardsson's "Description of Greenland". Taylor:

- In the "Description of Greenland" we read, for example: "Further north of the Western Settlement is a huge mountain called Hemebrachi, beyond which no one who values his life dares navigate, because of the number of whirlpools with which that sea abounds." "That sea", of course, was Davis Strait...

Davis Strait by Cnoyen:

- Also he said that the sea which lay on the east side could never be frozen because so many channels united there. And it was narrow besides, so that the current was very strong. But that the one which ran on the west side used to freeze almost every year: and remained frozen sometimes for three months. And in that land he had seen no signs of habitation.

No doubt the east is Greenland and the west Baffin Island. So it is Davis Strait. Like Bardsson, Cnoyen mentioned an important mountain near a discouraging whirlpool too:

- In the midst of the four countries is a Whirlpool... into which there empty these four Indrawing Seas which divide the North. And the water rushes round and descends into the earth just as if one were pouring it through a filter funnel... Except that right under the Pole there lies a bare rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic stone. And is as high as [the clouds?] so the Priest said, who had received the astrolabe from this Minorite in exchange for a Testament. And the Minorite himself had heard that one can see all round it from the Sea: and it is black and glistening. And nothing grows thereon, for there is not so much as a handful of soil on it.

The irritating fact about the magnetic mountain is its position "right under the Pole". All read it as under the North Pole. But the Minorite monk only heard about it - he never saw it. But if this mountain is the same as in Bardsson's Description it offers a very different interpretation.

Some historians suggested that Bardsson's mountain may be northwest of the Greenland settlements at the other side of Davis Strait. Three mountains are there. The highest and most impressive is Mount Odin at Baffin Island. Bylot Island was suggested by Enterline. The Devon Ice cap at Devon Island may offer a rather smaller island for the rock itself.

A Roman globe depiction of c. AD 50 with a north pole mountain, like magnet mountains from later times. (Click

here for full description.)

Taylor summarized the main facts: "The four indrawing seas separated four land areas, of which two (as Mercator and Ruysch agree) were inhabited, and two not." Once the magnetic mountain is identified as west of Davis Strait further identifications are possible.

The northern most Indrawing Sea is Nares Strait and the land Ellesmere Island. Next Jones Sound and Devon Island. Below is Lancaster Sound (the common entrance to the Northwest Passage) and Baffin Island. Southernmost is Hudson Strait and Labrador.[56]

The island with the magnetic mountain is described in the middle of the four lands. That would fit Devon as the smallest island above and excludes it from the list. Now Greenland is one of the four. That supports the report's description that two countries (Greenland and Labrador) "were inhabited, and two not." (Ellesmere and Baffin Island).

The identification of the four lands with the four main Arctic islands there[57] agrees with the four indrawing seas as the four main Straits there and the position of the magnetic pole near Devon Island.

The southern indrawing sea is Hudson Strait, and now the reported event in 1364 makes sense. Cnoyen according to Mercator: "But in A.D. 1364 eight of these people [from beyond the indrawing seas] came to the King's Court in Norway. Among them were two priests, one of whom had an astrolabe..."

They all went through Hudson Strait. Some of the eight were probably from those "10 men by the inland sea to look after our ships fourteen days journey from this peninsula" the Kensington Runestone in 1362 mentioned.[58]

So the Cnoyen report is one of several records for a pre-1600 European expedition in the Hudson Bay.

The other evidence:

- The various pre-1600 maps of Hudson Bay.

- The Verandrye find of a rune tablet in North Dakota.

- The 18th century Mandan cultural and genetic link to Europe.

- The Kensington runestone and the related artifacts found in the region.

J. R. Enterline saw evidence for cartographic knowledge of Hudson Bay in the map of Ruysch and the globe of Behaim.[59] Behaim's arctic had some similarities that suggest he had used the Cnoyen report too.

Before the King Arthur portolan link was found it was suggested that the map depiction of Hudson Bay was a holdover from classical times like Alaska and Antarctica. Now a creation in the 1360s seems possible. A third possibility is the presence of a map transmitted from classical times that triggered the 1340s Greenland events. That would explain the knowledge of the main arctic islands -- knowledge we do not have in Norse sources and which was then very difficult to acquire.

The Gestae Arthuri

The most puzzling part of the Mercator letter is the repeated reference to a book called "Gestae Arthuri" (GA). The GA described two attempts by King Arthur to conquer or colonize the Arctic around 530.[60]

It was about Iceland, "Grocland" and islands at the "Indrawing Seas" around the North Pole. The GA is no longer extant and the letter is the only information about it.

John Dee used the letter and other Arthurian legends to claim priority rights on the Arctic for the Elizabethan England.[61]

Mercator's mention of the GA was such a perfect play for Dee that the suspicion must arise Mercator simply invented this part of the Cnoyen report. But that was ruled out by Thomas Green, a specialist in Arthurian legends. He recently did the most up to date investigation on the Gestae Arthuri.[62]

Green found other Arthurian legends in the 14th century that mentioned Arthurian conquests in the north too. Two were from around 1200[63] but the GA itself was probably older.[64] Could the GA with its Arctic tale really be from the 6th century?

A Norse Origin?

It was already suggested by Skelton in 1965[65] and supported by Green that the GA was based on the Norse Greenland saga of Eirik the Red around 982. Eirik did a discovery mission and afterwards colonized Greenland with a fleet of 25 ships of which he lost 11 ships by a storm. According the GA Arthur sent 12 ships and lost 5. But that seems to be the second attempt by Arthur. In the first he sent 4000 men to conquer "the Northern Islands".[66]

Strangely Arthur sent no discovery mission but two conquest missions, as if these lands were already known. That seems like no good link to the Norse Eirik saga. Another suggested link is still under investigation.[67]

The details of the Arctic, the four indrawing seas and the four islands around the north pole are an essential part of the GA. But there is no trace of any Norse saga with those elements. The lack of discovery in the GA is a further strong contrast to the Norse sagas. So at least for now a Norse link seems doubtful.

How old is the basis of the Gestae Arthuri?

The central part of GA is the Arctic conquest. According to Green, the oldest known link of Arthur and the Arctic "...are hints that a tale of an Arthurian attack upon a frozen, possibly far-northern, Otherworld fortress existed in pre-Galfridian Welsh tradition, which could well be relevant here."[68] "Pre-Galfridian" is the crucial point here. It means before Geoffrey of Monmouth published c. 1138 his book "Historia Regum Britanniae", which is the oldest known text that mentioned Arthur as an "imperial, far-conquering" king. Green (2012):

- "The concept of Arthur as a historical warrior of c. A.D. 500 first appears in the Welsh "Historia Brittonum" of 829/30, where he is described as the dux bellorum, ‘leader of battles’. However, the Arthur of this text is certainly not an overseas conqueror: his victories are all insular, supposedly fought against the Germanic invaders of post-Roman Britain."

For scholars in Arthurian legends the book by Geoffrey of Monmouth is the central starting point. This is under the assumption that no older text of King Arthur got lost in transmission. But the transmission of medieval texts in general follows the simple rule: the older the text, the more likely it is that it got lost. And there was another factor beside the test of time (see below).

Based on the present state of records about Arthurian legends it seems impossible to give a date for the GA with certainty. The core of the GA is very probably older than 1350 AD. Whether it dates in whole or in part from early medieval times cannot be said with certainty. Any qualified opinion on this question must be left for specialists in Arthurian legends.

The Lack of Discovery

A very important point in the GA is the lack of discovery. Unlike the Norse sagas that reported in detail the discovery voyages of Iceland (c. 860),[69] Greenland and Vinland, the GA has the knowledge of these lands as a precondition. That reminds us of the Irish knowledge of Iceland in 795 before the Norse discovery.[70] Again there is no mention of any discovery. It was just ancient knowledge then. Per Traces of a Classical Portolan World Map it seems certain that the classical knowledge included Iceland, Greenland and America. From Britain and Ireland the next big island was Iceland and any knowledge about it had some practical value to persist here. It was not possible to erase it by burning books.

By the same reasoning a map of the North was more useful here than anywhere else in Europe. The existence of such a map seems more plausible than a real colonization attempt in 530. The whole GA may just be an invention to explain the map's existence. To attribute it to a Christian King Arthur was convenient and more acceptable than to the magicians of the pagan Roman Empire.

So the problem then was not the pagan classical origin but that the map allowed settlers to leave serfdom and tax burden for a new world not under state control. The 1340s events illustrated why such a map - if it existed - had to be hunted down and destroyed.

The Lost Records

The Mercator letter is outstanding because on a few pages it refers to several very important but no longer extant records. The Inventio Fortunata book is just the most famous because it was involved in Columbus' discovery of America. Further is the Gestae Arthuri, probably the Description of Greenland by Ivar Bardsson and the lost royal court record of the 1362 Hudson Bay expedition. Did all these most outstanding records get lost by chance?

For early medieval texts of King Arthur we have to suspect a selecting hand in the transmission. Regarding secular tales there is a factor known from 9th century Germany. Emperor Charlemagne around 800 ordered to record the legends of his people "barbara et antiquissima carmina, quibus veterum regum actus et bella canebantur" (Vita Karoli, c. 29) and he assembled a library with an extraordinary collection of Latin pagan books dating back to the 4th and 5th century. Copies out of this collection are the bulk of our Latin classical heritage. After his death in 814 the library was dissolved. These books and the collection of legends were destroyed. Remarkably, we have no direct record of the destruction.[71] But the motivation seems obvious. Charlemagne's successor is known as Louis the Pious. He ordered that "Poetica carmina gentilia" shall be neither read nor taught.[72]

It seems certain that the destruction happened either on order or with the consent of the new Emperor. A central hand of ecclesiastical influence through this event cannot be denied. Those tales we have could only be a fraction of what existed. The systematic preservation only happened after secular scribes and writers developed as a persistent part of the nobility. In Germany this was around 1200.

By the hero tales known from around 1200 a rationale for the previous ecclesiastical censorship became obvious, because now Christian topics were often a sideshow or completely absent. One of the most celebrated German writers then had Arabic elements in his tales, propagated friendship with Arabs at the high point of the crusades and invented a third class of "neutral angels".

Had such tales come up earlier they would have been a clear obstacle for the early medieval struggle to cover Europe with a unified Christian system of faith. To destroy them was the only practical way then. So Geoffrey of Monmouth's story of a Christian super king guided by a pagan magician may just be the first edition that survived.

The motivation regarding another record issue was different. In 1121 the Bishop of Greenland, Eirik Gnupson, visited Vinland.[73] One source (Lyschander; Gronlandska Chronica) mentioned that the Bishop brought colonists and Christian faith to Vinland. Hennig noted that such a voyage could only happen as part of direct episcopal duties. So the colony there had to be of considerable size, maybe like the Greenland settlements. Nevertheless the knowledge about Vinland in Europe was very sparse. The book by Adam of Bremen about the discovery seems the only known Vinland record in central Europe. The Vatican records seemed lost, some possibly rather recently,[74] and no copies or summaries are known.

For the European aristocracy and the Vatican the problem with Vinland was the same as with Hudson Bay. Any settlement there had an extremely large, uncontrollable hinterland where the serfs could find their freedom. Instead of a colony that produces tax revenues it would be drain Europe of its serfs. And serfs were the main engine of the European economy then. From that perspective the secrecy and the lack of records about medieval America becomes understandable.

But after the official discovery of America in 1492 the previous censorship of that knowledge was itself a new problem. Besides the delay of a new epoch for centuries a more grim issue became apparent. The secrecy about America contributed to the overpopulation of Europe that caused the Black Death in 1348. The death of about every third was the greatest loss of life in European history. That is a further reason to still label all pre Columbian America related records as unwanted. Therefore the loss of key sources was probably no accident and still an issue in modern times:

- The Inventio Fortunata was still extant around 1578 because George Best read it.

- Thomas Green suggested the Gestae Arthuri would still be extant in the 1570s.

- The Cnoyen report got lost after 1569.

- Most suspicious is the loss of the rune tablet found 1738 by de la Verandrye. He did not mention it in the printed book of his journey. But he gave a "personal report" to Kalm in 1749 who confirmed it through talks with other members of that expedition, and with Jesuits who investigated the tablet in Canada. Kalm wrote about it and made further inquests. He was told the tablet was sent to Count Maurepas in France. Inquiries there (even later by Alexander von Humboldt) got no results. That the Jesuits called it Tartar script - implying they had no knowledge of Norse runes - seems suspect. That no copy or drawing was kept in Canada is not credible.

Conclusion

Cartometric analysis of northern portolans and the Pizigani chart brought evidence for a lost portolan map of the northern hemisphere, from the Baltic to America. It was based on a 5 by 5 gon grid like the southern portolans.

The projection parallel was off center at 50° N, which pointed to the English Channel area as place of creation. The ability to handle an equirectangular projection and a gon grid points to the time of late antiquity. The lack of geographic details (like the Gulf of Kos) suggests a time well after the main book burning of the later 4th century. The resulting time window 470 - 600 fits well the time of the King Arthur legend.

Other evidence suggested that Gerardus Mercator was aware of the portolans' ancient origin. In a letter of 1577 he cited a medieval travel report by Jacobus Cnoyen that mentioned a book about arctic naval operations of King Arthur in 530. This Cnoyen report involved real events 1341 - 1364 in Norway, Greenland and America that were linked with geographic information about the Canadian Arctic.

There is evidence that the book Inventio Fortunata mentioned by Cnoyen was not limited to the North but may have had information on Central America latitudes too. The Cnoyen report described the creation but had no information from inside the Inventio Fortunata. This book played a role in the rediscovery of America by Columbus 1492.

The geographic information of the Cnoyen report about the Canadian Arctic was probably known before the Greenland 1340s events and came mainly from the Gestae Arthuri. A Norse source for the Gestae Arthuri geography is not known but a Welsh link to an early medieval King Arthur legend could be relevant. The information about the arctic came without mention of any discovery, and the lack of any medieval source points to a classical map as a possible source.

Surprisingly many records related to medieval knowledge of America are lost today. There is circumstantial evidence that this knowledge was kept restricted during medieval times and the loss of records did not happen by accident. That is a factor not yet in the focus of current research.

According to the present state of research, we have no direct records of any maps that were involved. But with the knowledge that a deliberate suppression of records happened, a find in neglected or misunderstood sources may still be possible.

Notes

- Jump up ↑ Lang (1986), p. 17 reported about a map collection by Jan Jansz alias de Paep of 1532 covering Europe from France (Bretagne) to the Baltic (Danzig). That would fit the suspected area of the main part of the 50° N map. But the known references raised doubt whether these were even maps or written descriptions only.

- Jump up ↑ That would cover the northern Azores which are more detailed on the southern map. The good match in rotation of only 1.75° of the 50° projection piece on the Pizigani was already feasible with a 43° N end that included the northern coast of Spain. So the evidence we have is well explained by a map that only went south to c. 39° N.

- Jump up ↑ The Gulf of Kos issue of the Pizigani chart points to a world map, Traces of a Classical Portolan World Map to a three panel pinax that carried the world map.

- Jump up ↑ Despite recent apologetics this is proven in the dissertation of Ernest Brehaut: An Encyclopedist of The Dark Ages - Isidore of Seville. Columbia University, New York (1912). The relevant excerpt can be found on Bibhistor's German Wikipedia page. Isidor no longer understood the meaning of the Latin words in the classical texts he had.

- Jump up ↑ Ward-Perkins, Bryan: The Fall of Rome; And the End of Civilization, Oxford (2006), pp. 104f, pp. 118f

- Jump up ↑ Euclid's text was erased in the 8th century in or near the monastery of Luxeuil and overwritten with Christian theology. It is known as Codices Latini Antiquiores 4,501. It was presented years ago by Bibhistor as evidence for a today unknown center of classical learning around 500.

- Jump up ↑ Cod. Theod. 9,16, 12 (= Cod. Iust. 1, 4, 14): mathematicos, nisi parati sint codicibus erroris proprii.

- Jump up ↑ Riche, Pierre: Education and Culture in the Barbarian West, (1976) pp. 44ff.

- Jump up ↑ Cotton MS Vitellius C. VII, fols. 264-269

- Jump up ↑ The missing lines can now be supplied from Dee’s recently discovered Latin translation and abbreviation of the letter. See: MacMillan, Ken and Abeles, Jennifer: "John Dee, The Limits of the British Empire", (2004), pp. 83-85. (So Thomas Green. He used this find to supplement the Gestae Arthuri parts in 2012.)

- Jump up ↑ E. G. R. Taylor, "A Letter Dated 1577 from Mercator to John Dee," Imago Mundi (Amsterdam, 1956), 13, pp. 56-68

- Jump up ↑ "Norse" is used interchangeably with "Norwegian" in this document.

- Jump up ↑ This information about Best is from: Prytz, Kare: Westwards before Columbus, Oslo 1991, p. 80. He mentioned parts of the following citations, too.

- Jump up ↑ p. 34 in: "A True Discourse of the Late Voyages of Discoverie for Finding of the Passage to Cathaya by the North-Weast, under the conduct of Martin Frobisher General, London (1578)" found reprinted in: "The Three Voyages of Martin Frobisher: In Search of a Passage to Cathaia and India by the North-West, A.D. 1576-8 (Cambridge Library Collection - Hakluyt First Series) by Richard Collinson (Apr 22, 2010), ISBN-10: 110801075X ISBN-13: 978-1108010757 (Main parts visible at Google Books)

- Jump up ↑ The citation in context: "a frier of Oxforde... described almoste all the lande aboute the Pole, finding it divided into foure partes or ilandes by foure greate guttes, indrafts, or channels...Hee reporteth that the south-weast parte of that lande is a fruitfull and a holesome soyle. The north-east part (in respect of England) is inhabited with a people called Pygmaei, whiche are not at the uttermoste above foure foote highe." Best (1578), pp. 34f.

- The context shows the word "lande" does not mean one of the four parts or islands but the whole region with all four together, Therefore the "south-weast parte" could not mean the south-west of Greenland. There was agriculture in the south but they had no knowledge about the north-east of Greenland. The Inuit were at the west and north of the island. They had contact with the Norse at the west coast down to the western settlement. The Norse could not reach the north-east of Greenland, neither by ship nor by land.

- Jump up ↑ Taylor was not aware that George Best wrote about the Inventio Fortunata. She mentioned him only regarding the description of Davis Strait: "That sea", of course, was Davis Strait, and when Frobisher was at its mouth, his lieutenant George Best reports: "This place seemeth to have a marvellous great indrafte, and draweth in to it most of the drift ice and other things which doe flote in the sea." Taylor (1956), p. 68.

- Jump up ↑ Because in the next sentence Best wrote: "The north-east part (in respect of England) is inhabited with a people called Pygmaei, whiche are not at the uttermoste above foure foote highe." This is Greenland. The directions given are not "in respect of England" but "comming from England" to an approach point between south Greenland and Newfoundland. A point like the then deserted Norse station at L'Anse Aux Meadows would fit. But the area there is only forest, nothing "fruitfull". Vinland was located below 43° N because that is the northern limit of vine grow.

- Jump up ↑ Prytz (1991), p. 80. After I found the reference to George Best to be correct, I felt assured to rely further on Kare Prytz' work without additional source checks.

- Jump up ↑ Prytz: "As a young adult Columbus happened upon something that completely changed his life: A book about America. A sailor who went with him on the first three voyages to the New World and who later ended up in Turkish imprisonment, said that it was a coincidence that Columbus came upon the book - and that in it he found all the information he needed for his famous voyage to the West Indies." Prytz (1991) p. 97

- Jump up ↑ Prytz: "«The Admiral's Book» is mentioned by Columbus himself in his diary - for instance during the voyage entries from September 25, October 3, and October 10 of 1492. At this time there was only one book in existence about America, and that was Inventio Fortunatae," Prytz (1991) p. 97. I could not find it in a German translation of Columbus' ship diary. But I heard from a historian involved with that book that different text editions exist.

The evidence from available secondary sources that Columbus had read the book before his first voyages is only circumstantial. What's certain is that, according to a 1498 letter from the English merchant John Day, he unsuccessfully asked him about a copy later. See Williamson, James A.: "The John Day Letter", The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery Under Henry VII, Cambridge (1962)), pp. 212-214

- Jump up ↑ Together with a 1498 map of Columbus, possibly a parrot feather hat from America and an axe made of hard black stone that could cut iron. It probably happened near Valencia where a Turkish fleet took seven Spanish vessels. Inan, Afet: The Oldest Map of America, Ankara (1954) p. 21-27

- Jump up ↑ Complete Text:

V. This section tells how these shores and also these islands were found. These coasts are named the shores of Antilia. They were discovered in the year 896 of the Arab calendar. But it is reported thus, that a Genoese infidel, his name was Colombo, be it was who discovered these places. For instance, a book fell into the hands of the said Colombo, and he found it said in this book that at the end of the Western Sea [Atlantic] that is, on its western side, there were coasts and islands and all kinds of metals and also precious stones. The above-mentioned, having studied this book thoroughly, explained these matters one by one to the great of Genoa and said: "Come, give me two ships, let me go and find these places." They said: "O unprofitable man, can an end or a limit be found to the Western Sea? Its vapour is full of darkness." The above-mentioned Colombo saw that no help was forthcoming from the Genoese, he sped forth, went to the Bey of Spain [king], and told his tale in detail. They too answered like the Genoese. In brief Colombo petitioned these people for a long time, finally the Bey of Spain gave him two ships, saw that they were well equipped, and said:

"O Colombo, if it happens as you say, let us make you kapudan [admiral] to that country." Having said which he sent the said Colombo to the Western Sea. The late Gazi Kemal had a Spanish slave. The above-mentioned slave said to Kemal Reis, he had been three times to that land with Colombo. He said: "First we reached the Strait of Gibraltar, then from there straight south and west between the two . . . [illegible]. Having advanced straight four thousand miles, we saw an island facing us, but gradually the waves of the sea became foamless, that is, the sea was becalmed and the North Star--the seamen on their compasses still say star--little by little was veiled and became invisible, and be also said that the stars in that region are not arranged as here. They are seen in a different arrangement. They anchored at the island which they had seen earlier across the way, the population of the island came, shot arrows at them and did not allow them to land and ask for information. The males and the females shot hand arrows. The tips of these arrows were made of fishbones, and the whole population went naked and also very . . . [illegible]. Seeing that they could not land on that island; they crossed to the other side of the island, they saw a boat. On seeing them; the boat fled and they [the people in the boat] dashed out on land. They [the Spaniards] took the boat. They saw that inside of it there was human flesh. It happened that these people were of that nation which went from island to island hunting men and eating them. They said Colombo saw yet another island, they neared it, they saw that on that island there were great snakes. They avoided landing on this island and remained there seventeen days. The people of this island saw that no harm came to them from this boat, they caught fish and brought it to them in their small ship's boat [filika]. These [Spaniards] were pleased and gave them glass beads. It appears that he [Columbus] had read-in the book that in that region glass beads were valued. Seeing the beads they brought still more fish. These [Spaniards] always gave them glass beads. One day they saw gold around the arm of a woman, they took the gold and gave her beads.

From "The Oldest Map of America," by Professor Dr. Afet Inan. Ankara, 1954, pp. 28f

- Jump up ↑ "In the chapter on this 'Western Sea' we read all that is known about the discovery of America at the time. Of this he recounts, on hearsay again, how a certain book from the time of Alexander the Great was translated in Europe, and after reading it how Christopher Columbus went and discovered the Antilles with the vessels he obtained from the Spanish goverment." Inan, Afet: The Oldest Map of America, Ankara (1954) p. 21

- Jump up ↑ *Involuntary storm rides of boats or small ships from Greenland and North America to European coasts were not uncommon. Sometimes Indians even survived the crossing like in the oldest recorded case from Romans in 62 BC. Hennig, Vol 1, 1944, pp 289ff

- An archaeological find in Mexico proves contact and may suggest trade in the 3rd century AD. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca_head This find can not have been caused by a storm wrecked ship because any such ship would hit Florida or the Caribbean islands. To reach Mexico, a European ship must have voluntarily passed these islands or Florida Strait.

- Isidor of Seville (c. 630): "There lies another continent besides the three known ones, beyond the ocean, far up north, and there the sun is warmer than anywhere in our country" (Etymologies, Bk. 14, Chapter 5). According to Afet (1954) p. 55. Translation (of another text version?) by Barney, Lewis, Beach and Berghof, Cambridge (2006): "17. Apart from these three parts of the world there exists a fourth part, beyond the Ocean, further inland toward the south, which is unknown to us because of the burning heat of the sun; within its borders are said to live the legendary Antipodes."

- Jump up ↑ Prytz (1991) pp. 164f.

- Jump up ↑ It was in a "Reed year" of the Mexican calendar that repeats every 52 years. In the Reed year of 1519, as Cortes arrived, "Montezuma said that several generations had passed since the visit took place." So: 1519 - 1467 - 1415 - 1363.

- Jump up ↑ Prytz: "He [a priest] left in a long boat, that looked like a snake, and with a stem formed as a falcon's head. It was built "like the feathers of a bird", with boards overlapping. It seems to be an accurate description of the characteristic clinker-built Norse long ship. Even the name is reminiscent - the most famous of all Norwegian long ships was called "Ormen Lange" [The Long Snake] and was owned by Olav Trygvasson. When he [a priest] left the land headed east, he said he would be back."

- Jump up ↑ Prytz (pp. 157f): "In an original document from 1566 the Spanish missionary, monk and later bishop, Diego de Landa, notes the following in his report Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan: *«...besides all this, I must tell what was told me by the chiefs of the Indians - a man of high intelligence who had the respect of all [the inhabitants]. One day I was speaking with him, I asked if he had ever heard about Christ, our Lord, or about the cross. He said that from his forefathers he had not heard of either Christ or the cross - except for one time when some of his people tore down a little house all the way out on the coast. Inside the house there were some graves, and on the bodies or bones of the dead there were small metal crosses. Since then they have seen no crosses until the day they were christened and saw the cross worshipped and adored. They therefore thought that those dead men had also worshipped the cross. If this was so, it is most likely that the little group had come from our land of Spain, and had thereafter disappeared without a trace.»" Prytz further writes: "The place referred to, is Cap Catoche on the northern tip of the Yucatan, the point closest to Florida. And the small house must have been a house of worship - perhaps a little missionary church?"

- Jump up ↑ Prytz (1991) p. 97

- Jump up ↑ J. R. Enterline: "Erikson, Eskimos, and Columbus: Medieval European Knowledge of America" Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2002. Enterline referred to:

- Helge Marcus Ingstad, The Historical Background of the Norse Settlement Discovered in Newfoundland, vol. 2 of Norse Discovery (Oslo: Norwegian Univ. Press, 1985), pp. 377-78, 392;

- Kirsten Seaver, The Frozen Echo (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Univ. Press, 1996), p. 134.

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), p. 438

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), p. 345; Enterline (2002), p. 129

- Jump up ↑ Enterline (2002), p. 129

- Jump up ↑ But only extant in a third person report. Enterline (2002), p. 129

- Jump up ↑ Text by Enterline (2002), p. 129 and Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), p. 326. Hennig's source: "Gisle Oddson's Isländische Annalen zum Jahre 1342, nach Gustav Stonm: Om Biskop Gisle Oddsons Annaler, im Arkiv for Nordisk Filologi VI, Lund 1890, 355f."

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), p. 342

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), p. 351

- Jump up ↑ Complete text of the king's order in German in: Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), pp. 324f. It is the last record about Knutson, who played a "considerable role" (Hennig) in the history of his country. It was pointed out that we have no record that the Knutson force really left port. But we have strong circumstantial evidence. Hennig pointed out that Ivar Bardsson could only be back in Norway 1364 if the Knarre sailed 1355 or soon later. There was no other voyage. Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), p. 351. His source: "Gustav Storm: Vinlandsrejserne, 74."

- Jump up ↑ Its authenticity is disputed by some linguists today. But it is not true that "every Scandinavian runologist and expert in Scandinavian historical linguistics has declared the Kensington stone a hoax" (Wikipedia 2011). According to Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), pp. 324ff several runologists judged it to be authentic or possibly authentic. The find circumstances in 1898 were investigated by Holand and other related finds (weapons, armor, a boat wreck, etc.) convinced the Smithsonian Institute in 1949 of its authenticity. If the stone and related finds are hoaxes it would by a large margin be the greatest archaeological hoax in history.

- Jump up ↑ Gotland was part of Norway then.

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, p. 351

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, Vol. 3, (1953), pp. 327ff. His source: Forster: Kalm's Travels into North America, translated into English by J. R. Forster, London 1771, III, 122 ff.

- Jump up ↑ From the diary of Sieur de la Verandrye (1738), Hennig pp. 328ff. His source: English translation by Brymner in "Report on Canadian Actvities, Ottawa 1889/90, p. 3 ff. About 9 towns in 1773 and agriculture: Hennig p. 332

- Jump up ↑ D. D. Mitchell, director of the department of Indian Affairs, c. 1830. Hennig p. 330. His source: H. R. Schooleraft: History, condition and prospects, Philadelphia 1851, III, pp. 253f.

- Jump up ↑ Hennig p. 332. His source: "George Catlin: O-Kee-Pa, a religious ceremony, Philadelphia 1867, 5."

- Jump up ↑ Hennig p. 330. His source: George Catlin: Letters and Notes on the manners, customs and conditions of the North American Indians, London 1841, I 93:

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, p. 332

- Jump up ↑ Hennig, p. 347

- Jump up ↑ In 1121 the bishop of Greenland even visited Vinland. Hennig, Vol. 2, (1952), pp. 384ff

- Jump up ↑ "And there are many small rivers, some two, some one, some three kennings [Taylor: A kenning was 17-20 miles] wide, more or less: and they are called "indrawing seas" because the current always flows northwards so strongly that no wind can make a ship sail back against it. And here it is all ice from October to March."

- Jump up ↑ King Arthur finally "peopled all the islands between Scotland and Iceland, and also peopled Grocland." (Taylor translation). Note that Mercator thought Grocland to be an island just west of Greenland. But in the context of the report it must be Greenland.

- Jump up ↑ Enterline (2002), p. 57

- Jump up ↑ The archeologist Uwe Müller in 2005 suggest for 1360 the magnetic pole to be "something like 12° East of today". He based it on a paper: Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 108, NO. B2, 2078, doi:10.1029/2002JB001975, 2003.

- Jump up ↑ The oldest extant (western) text to mention the compass was by Alexander Neckam in c. 1180. The magnetic mountain at the north pole is first mentioned by the poet Guido Guinizelli in 1276. See Duzer, Chet Van. "The Mythic Geography of the Northern Polar Regions: Inventio fortunata and Buddhist Cosmology." Culturas Populares. Revista Electrónica 2 (mayo-agosto 2006), http://www.culturaspopulares.org/textos2/articulos/duzer.pdf p. 7 note 9.

- Jump up ↑ The transmitted classical texts have no mention of the compass. Just magnets, magnetic mountains and even magnetic islands - but none at the pole. Nevertheless a fresco from Pompeii shows a globe with a high mountain at the north pole. That could suggest a removal of the compass from our transmitted texts in the early Middle Ages.

- Jump up ↑ Labrador has a lot of forest but only in south Labrador the trees reach the coast. The northern and eastern coast look very poor and were probably the stony "Helluland" of the Norse saga. In south Labrador and Newfoundland the forests reach the coast; it was the Norse "Markland". They used the wood there for centuries. The Cnoyen report covered Markland because it mentioned: "There are many trees of Brazil wood."

- Jump up ↑ Labrador is a peninsula, but that is not very obvious.

- Jump up ↑ The 1342 captured fled settlers were probably sent to Norway before the Knutson expedition was launched. Knutson's Kensington force probably got lost without a chance to capture more settlers. Rather their forced guides may have had a chance to escape. The position of Kensington in respect to the Mandan area indicates they were misguided or already without guides then.

- Jump up ↑ "As previously shown, the Behaim globe seems to contain information about the American North, and there indeed is an inland sea in North America, Hudson Bay. Behaim does not show it in the right shape or in exactly the correct relative location within the continent and does not show any connecting strait, but its very presence and size are suggestive. The Ruysch map (Figure 54) shows a similar inland sea of almost identical shape labeled Mare Sugenum, 'Indrawing Sea.'" Enterline (2002), p. 59

- Jump up ↑ Mercator: "That great army of Arthur's had lain all the winter (of 530 AD) in the northern islands of Scotland. And on May 3 a part of it crossed over into Iceland. Then four ships of the aforesaid land had come out of the North. And warned Arthur of the indrawing seas. So that Arthur did not proceed further, but peopled all the islands between Scotland and Iceland, and also peopled Grocland. (So it seems the Indrawing Sea only begins beyond Grocland)." Taylor (1956), p. 58.

- Jump up ↑ He saw it especially important for the rights to the Northwest Passage to Asia that was expected to be found in the Canadian Arctic. See Ken MacMillan and Jennifer Abeles: "John Dee: The Limits of the British Empire" (Studies in Military History and International Affairs) (Dec 30, 2004)

- Jump up ↑ Thomas Green, "John Dee, King Arthur, and the Conquest of the Arctic", Heroic Age, 15 (2012), http://www.heroicage.org/issues/15/green.php

- Jump up ↑ "Although the Leges was composed c. 1210, the closely related but fragmentary "Insule Britannie" (the earliest manuscript of which dates to c. 1200) indicates that this concept of Arthur [an Arthur who "conquered the whole of the Arctic far-north"] probably ante-dated both the composition of the Leges and the thirteenth century." T. Green, "An Alternative Interpretation of Preideu Annwfyn, lines 23-28", Studia Celtica, 43 (2009), 207-13. p. 8

- Jump up ↑ "The date of this Gestae Arthuri is naturally uncertain given how little of it survives, but its tale accords well with the allusions in the Leges and it seems most likely that either the lost Gestae Arthuri was the source of the Leges or both derive from a common source written in the twelfth century." Green (2009), p. 9

- Jump up ↑ R. A. Skelton: "The Vinland map and the Tartar relation", (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), p. 244.

- Jump up ↑ Taylor translation: "(Lacuna) ... part of the army of King Arthur which conquered the Northern Islands and made them subject to him. And we read that nearly 4000 persons entered the indrawing seas who never returned." Side note by Dee: "4000 of King Arthur's subjects consumed with the Indrawing seas."

- Jump up ↑ The GA mentioned that Arthur encountered "people 23 feet tall" in Grocland. Gwyn Jones, (‘The Vikings and North America’, in "The Vikings", edited by R. T. Farrell (London: Phillimore, 1982), pp. 219-30 at p. 222.) states that "early Greenland sources tell of natives... 23 feet tall’". Unfortunately Jones' paper lacks detailed notes and after several years Thomas Green was not able to identify the source text. In 2008 it was suggested that Gwyn may have confused it with the GA itself. Skelton, who first suggested the Norse link, was not aware of another source for the "23 feet tall". If ever found it could nail the GA to the Norse sagas. The odd 23 feet may originate in a transcription error of the description of Inuit children seen alone. The Norse described them ("Skraelings") as "small, often only 2 or 3 feet high" like dwarfs or elves (Nansen, Northern Mists). The GA mentions the Inuit, Cnoyen: "And near here, towards the north, those Little People live of whom there is also mention in the Gestae Arthuri." (Taylor Translation).

- Jump up ↑ Green (2012). The full discussion of this reference can be found in Green (2009).

- Jump up ↑ Hennig vol 2 (1952), p. 186

- Jump up ↑ Dicuil reported a visit by Irish monks in Iceland to convert the pagans there. They left some material behind that got mentioned as a find in later Norse sagas. All according to Hennig vol 2, (1952), pp. 130ff

- Jump up ↑ According to the only record (Vita Karoli) the library was sold to feed the poor. An absurd suggestion in an agrarian subsistence economy. We know a destruction happened because the text and paintings from inside the books were no longer copied. Only copies from copies were created after 814. From some books the impressive decoration of the book cover survived but not even fragments from inside pages. The destruction of the parchment pages was probably done by fire, because no palimpsests were ever found. That the codices vanished by "neglect" is impossible. Stored like most others they would well have survived. (I have to thank Bibhistor for this information.)

- Jump up ↑ By "gentilia" it included classical pagan texts too.

- Jump up ↑ Hennig vol 2 (1952) pp. 384-395

- Jump up ↑ Hennig found citations by 19th century church historians but was unable to find the source records in the Vatican archive. Hennig vol 2, (1952), pp. 389ff